Gallstones

Gallstones are very common in Australia. Most patients with gallstones may not know they have them and may never need surgery for them if there have been no symptoms. If you have been diagnosed with gallstones, it will most likely be for one of the following two reasons:

- 1. You had symptoms or blood test results that made your doctor think you need further tests and this led to the scan that diagnosed your problem or….

- 2. Your gallstones were coincidentally found on a scan that was performed for another reason.

Regardless of how your gallstones were found, once you know they exist, you need to discuss this firstly with your GP and if she or he thinks it necessary, then a discussion with a surgeon who regularly deals with gallstones may be needed.

The following information explains the role of your gallbladder, what gallstones are, the possible symptoms gallstones can cause and the surgical treatment options available if required.

The Gallbladder

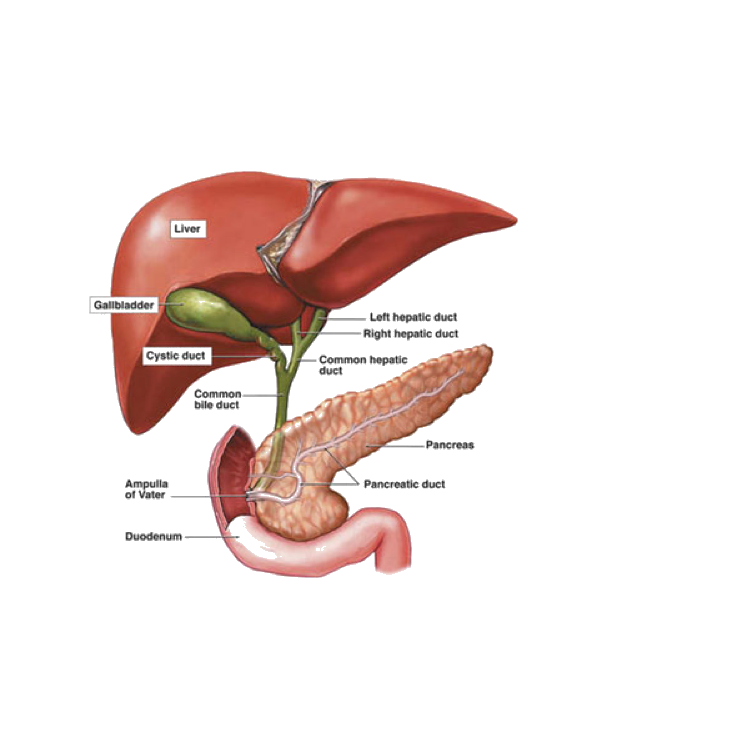

The gallbladder is a part of your digestive system. It is involved in the storage of bile made by your liver.

Your liver and gallbladder are located in your upper abdomen, just under your right ribcage. Your liver produces bile and this bile leaves the liver through a series of ducts to pass down the common bile duct and into the bowel where it mixes with the food you eat. Your bile has many different jobs to do in your body but one of the main things it does, is assist with the digestion of fats and oils that we eat. It acts very much like a detergent to help “dissolve” these types of foods.

Your gallbladder hangs off the side of the bile duct and acts as a storage organ for some of the bile your liver is always making. When you have a fatty meal (eg dairy food or oily foods), your gallbladder is sent a signal to squeeze and empty this extra stored bile down your bile duct and into your bowel. Your gallbladder does not make bile or remove it – it is purely a reservoir that just stores extra bile for when you may need it.

Gallstones are exactly what the name suggests – stones within the gallbladder. In some parts of the world, gallstones can occur in up to 10% to 15% of the population (mainly the Western and developed world) over a lifetime.

Most stones are made up of a mixture of cholesterol, bile pigments and calcium. They can range in size from very small stones, the size of a grain of sand; up to very large stones which can be centimetres wide. Generally, whilst different sized stones are more likely to cause different types of problems, you only need to have one stone of any size for it to cause a potential problem.

Once you have a gallstone, you generally have it for life unless you pass it out through your bile duct (which is a potentially dangerous situation) and into your bowel.

Only 20% of people with gallstones will ever have a problem with them in their lifetime. Most people will never know they have them unless they are discovered coincidentally with a scan for another reason. If you have never had symptoms, then our research shows that it is almost certainly safer to leave them alone and not have an operation (there are some exceptions to this). If this is the case though, please see your GP to discuss it and make sure there are no other issues to be checked prior to not taking things further.

If you do have symptoms however, it is certainly worthwhile seeing a surgeon regarding this. People who have suffered symptoms from their gallstones are nearly always better off having an operation to remove their gallbladder (a cholecystectomy) to relieve the symptoms and prevent further problems occurring in the future. There is very clear evidence that in most cases, removing the gallbladder in this situation is much safer for you. Most people with symptoms suffer from pain due to the stones blocking the neck of the gallbladder (biliary colic) but more serious problems such as an inflamed gallbladder (cholecystitis), a blocked bile duct causing yellow skin (jaundice) plus infection (cholangitis) and an inflamed pancreas (pancreatitis) can occur. These more serious problems are thankfully less common but once you have had pain, you are automatically at a higher risk of these potentially larger problems as time goes on.

By seeing a surgeon who is experienced performing cholecystectomy, a decision can be made, after you have been assessed, as to whether this is the correct option for you.

There has been much research into gallstones and their treatment over many thousands of patients and over many decades. Part of this research has looked at methods to treat gallstones that doesn’t involve surgery. Therapies to dissolve the stones with tablets (“dissolution therapy”) or break them up with ultrasound (called lithotripsy) have been tried with some limited success but the over-riding reason why most doctors no longer offer this to patients is the fact that the treatments are often unsuccessful and when they do work, gallstones often reappear within a couple of years afterwards.

We know that if you remove the gallbladder for gallstone disease, you will successfully treat the problem over 99.6% of the time. There are a very small number of patients who can form new stones in other places such as the bile duct, even after having their gallbladder removed or they can have a small stone left in the bile duct that was missed at the time of their operation. This chance is rare but not impossible. Despite this, there is currently no doubt that at present, a cholecystectomy is the best treatment for gallstones that are causing symptoms. By doing this surgery, the risk of the more serious problems listed above is nearly reduced to zero.

A cholecystectomy is an operation to remove the gallbladder.

It can be performed in one of two ways. Prior to 1985, nearly all the cholecystectomies in Australia were performed as an open procedure. That means that the operation was performed through a large, open incision in the upper abdomen.

For the last 25 to 30 years, most cholecystectomies in Australia are now performed with small “keyhole” incisions via a technique called laparoscopy (laparoscopic cholecystectomy). Laparoscopy has huge advantages over open surgery in terms of your recovery after the operation. It should be the preferred method wherever possible as you generally only need to stay less than 24 hours in hospital and you regain your mobility within a few weeks due to less pain. In addition to this, the cosmetic result is often better as the incisions are usually quite small for laparoscopy. With open surgery, your recovery is generally much longer as it tends to be more painful due to the larger incision. Regardless of which method is used though, the operation internally is essentially the same and the success and complication rates are also the same.

Approximately half of all patients who undergo a cholecystectomy do not feel any difference between having their gallbladder and being without it. In this situation, there is no problem with eating any type of food as your gastrointestinal tract is accommodating without it.

For the other half of patients however, being left without a gallbladder after a cholecystectomy can result in some changes after the surgery. In this situation, the majority of patients will find that particular foods such as dairy food, fatty food and many dessert type foods (often containing butter etc…) can cause a range of symptoms. These problems range from patients saying they have “a yuck feeling in the stomach” through to cramps and diarrhoea after eating these types of food. Most of the time, this is only a short-term problem and your ability to tolerate these foods after a few months, should improve. Rarely, this problem can be a longer-term issue (<2% of patients) but unfortunately there is no way of predicting prior to surgery, who will be affected in this way.

As with most operations, you will need to rest for a period of time after your procedure. In most circumstances after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, most people can return to a job with light duties within 2 weeks after the surgery. For jobs that involve heavy lifting or a lot of physical strain however, an extra week or two may be required depending on how you recover.

I normally recommend you do not drive for a week as well. If you still have significant discomfort after that time, you should not drive until the discomfort settles.